Site Leads in Ontario: Underutilized but Important Resources for Identifying Site Locations

Site Leads in Ontario: Underutilized but Important Resources for Identifying Site Locations

Information from landowners and local residents about the possible location of an archaeological site has long been an important resource for archaeologists. “Site leads,” or hearsay accounts of site locations deriving from local knowledge, often translate into the discovery of previously unrecorded archaeological sites. The early explorers of archaeological sites in the province often used site leads to find some of the most important Indigenous archaeological sites in Ontario, many of which were recorded in the early-20th century issues of the Annual Archaeological Report for Ontario (AARO). In addition to archaeological sites, site leads were sporadically published in the AARO. These early accounts are important today because they provide information on site locations in areas that have now been heavily impacted by modern development. Further, in some areas where there has been little archaeological survey to formally identify and register archaeological sites, local knowledge and site leads are the only pieces of information available about the location of archaeological resources. With this, “site leads” are a critical, but underutilized, element in cultural resource management in Ontario today.

Archaeologists have been working in Ontario for over one-hundred years but the systems we use for formally tracking the location of archeological sites are still relatively new. For example, PastPort, Ontario’s online archaeological data system, is barely five years old. Its predecessor, the Ontario Archaeological Site Database, had been developed a little more than a decade earlier. A previous iteration at a national level was run by the Canadian Heritage Information Network in the 1990s.

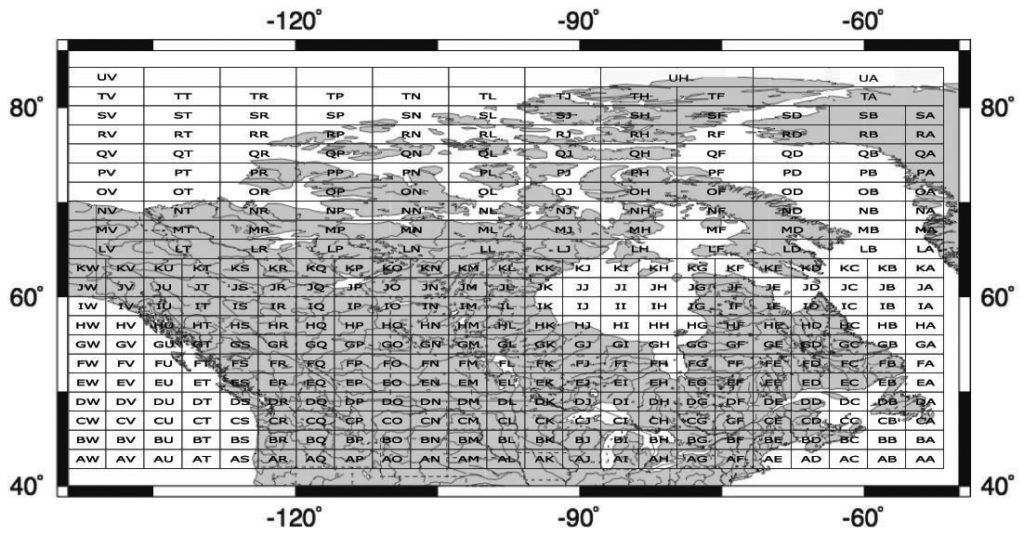

The Canadian Borden System

Even the geographical/sequential Borden Block system, the current designation system for identifying archaeological sites in Canada, only dates to 1952 (widespread in Ontario by the 1960s). Outside of their own schema of designations applied by the Archaeology Section of the Geological Survey of Canada in the early-20th century, archaeological sites were previously known only by name, if they even had those. Sites were often named after or at least referred to by the person or family who owned the land at that time (e.g., the Foster Farm site). Significant sites might be referred to in legislation, regulation or widely published literature; however, the majority of sites found between the late-19th century and 1950 only appear less accessible publications like the AARO and the unpublished field notes and maps of early avocational (non-professional) archaeologists. For example, many of the ancestral Wendat (Huron) occupation sites in old Huronia are known only from the 17th century writings of the Jesuits and the work of avocationals in the late-19th and early-20th century whose work is published in non-archaeological writings. The Huronia Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society acknowledges the importance of the work of these researchers and maintains a database of hundreds of non-registered potential site locations based on it. Since relatively little land development occurs in the rural portions of Simcoe County, where most of these sites were known to exist, this is an invaluable resource for both knowledge and planning.

Since the 1950s, and especially in the past 20 years, many early recorded sites have been rediscovered by commercial archaeologists working in advance of land development. In some cases sites are linked with their historic iteration, in others they are treated as new discoveries, their recent past forgotten. Many remain unacknowledged.

In recognition of this phenomenon, the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport implemented a Site Lead (s. 3.3.2) process as part of their PastPort system. Site leads were meant to track potential archaeological site locations known from local, hearsay or early avocational accounts but not visited and confirmed by licensed archaeologists. Ministry examples include:

- An agricultural field where a farmer has recovered artifacts but you (the licensed archaeologist reporting the lead) have not observed the artifacts in situ [in their original location].

- An archaeological site that is not listed in the Sites Database but is mentioned in historical documentary resources.

According to the Ministry, site leads “receive a unique tracking number” and appear in text searches within the PastPort system, however site leads do not appear in any mapping outputs. Despite the foresight of the Ministry to recognize the importance of site leads as an indicator of potential site locations, few archaeologists have actually utilized this resource. To date, around 50 site leads have been compiled, 30 by TMHC alone. Nonetheless, thousands of potential archaeological site locations are known throughout the Province from important avocational and archival documents. The registration of site leads in PastPort is currently an extraneous process and few archaeologists have had the incentive to use this tool. When considered at a regional level, like in the case of old Huronia, the entry of site leads would also be a very lengthy and expensive process. However, it remains a critical one as many sites are or will be threatened by pending development. The importance of site leads is not restricted to conventional archaeological sites either.

The Ontario Genealogical Society has been recording and documenting unregistered and abandoned cemeteries in Ontario for over a decade. To-date, thousands of these unregistered cemeteries have been identified and are valuable site leads to archaeologists. However, this wealth of information also has not been translated into site leads with PastPort even though doing so adds another level of legal protection for small or unmarked cemeteries that are not visually obvious on the landscape. On two separate occasions in recent years, TMHC has registered site leads for two early Black cemeteries that are neither well-known nor visible on the ground. In both cases, we were approached by concerned residents, descendants and researchers to help ensure the cemeteries would be protected and not impacted by new development. This was the case for the Johnson Family Cemetery in Halton County, an abandoned farmstead cemetery that is now overgrown by trees and was not kept up by the current landowner. The property was put up for sale and development is imminent. The OGS had recorded this family cemetery, which provided a valuable lead not only to the cemetery, but also the associated residence of a family with connections to the Underground Railroad. In 2018, TMHC staff created a site lead in PastPost so that commercial researchers that might be hired to clear the property for development would be made aware of the presence of an unmarked cemetery and a potentially significant farmstead site.

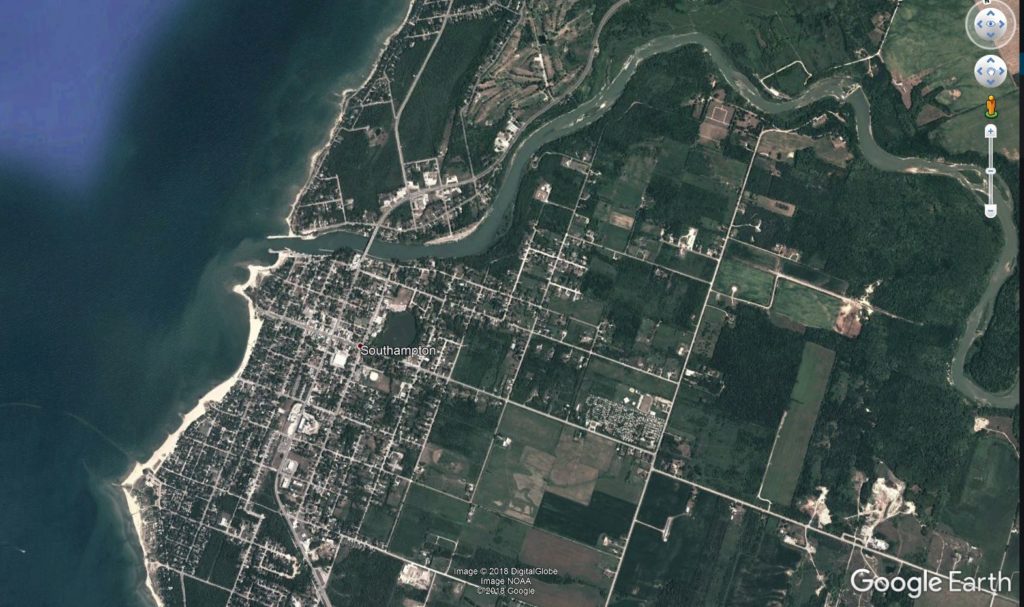

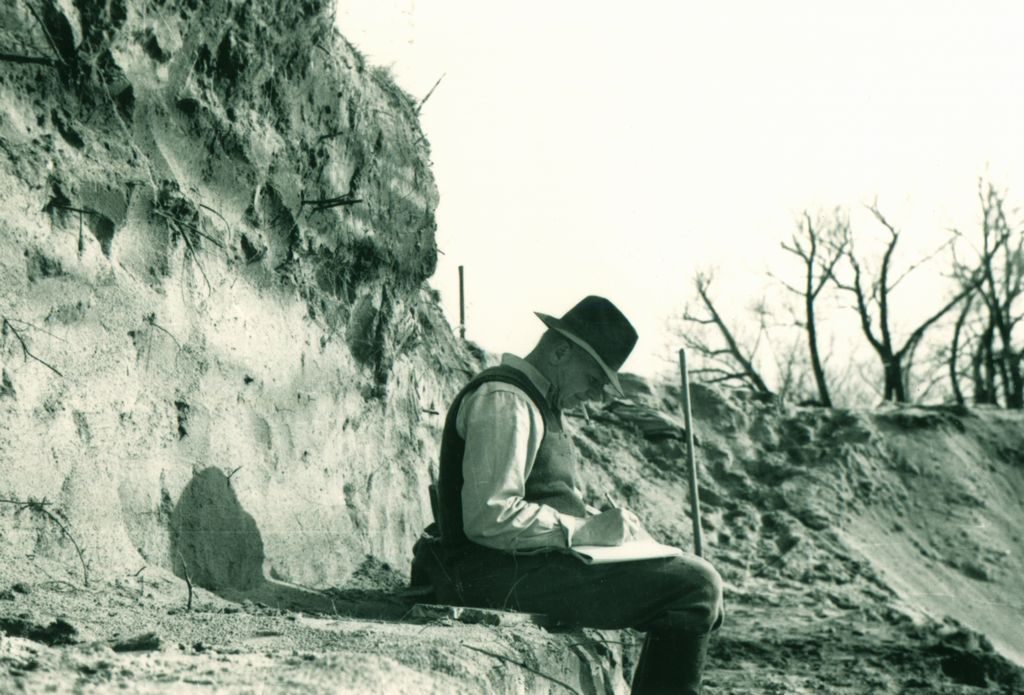

Entering a single site lead in PastPort is not that arduous. However, entering leads on a local or regional scale is much more daunting but nonetheless important. In the spring of this year, TMHC facilitated the entry of 24 site leads in the Southampton area, effectively doubling the total number of registered site leads registered with the Ministry at the time. Sites were located and georeferenced using the maps and notes of a local avocational archaeologist, D.B. Shutt, that are stored at the Museum of Ontario Archaeology. The documents map and describe numerous Indigenous settlement and burial sites along the Lake Huron shoreline. This activity resulted from the recent controversy surrounding a burial ground that Shutt had identified in the 1940s, but that only the local Saugeen Objiway Nation remembered existing. The site had never been relocated or registered since Shutt’s time but had a site lead been entered previously for the burials grounds, much of the ensuing difficulties might have been avoided. TMHC registered site leads for the remaining sites that Shutt had identified in Southampton to avoid repeating this scenario, however Shutt’s notes and maps hinted at sites in other places, most notably in the Kingston area. While pursuing further site leads from D.B. Shutt’s notes would be worthwhile, it would be an intensive process. Like other community museums, the archives at the Museum of Ontario Archaeology and in the Wilfrid Jury collection are full of local knowledge on site locations - but these are only be the tip of the early-20th century archaeological iceberg.

There are other, even larger collections of site locations, representing thousands of prospective site leads across Ontario. For example, the notes and publications of George Laidlaw are integral for understanding past Indigenous land use in northern Victoria County. Those of Tom Lee were used by Dana Poulton to re-find hundreds of sites in the Otter Creek drainage; however, by the time Poulton conducted his survey in the 1980s, many of Lee’s sites had long since been destroyed. The drawings and sketch maps of avocational archaeologist Ernie Sackrider assisted CRM archaeologists in relocating a major Iroquoian village and burial site on what was the old Foster Farm in west London. There only tiny remnants of middens and longhouse were preserved in a narrow park pathway sheltered from adjacent residential development. To date, this is one of the only Middle Iroquoian occupations documented in the city. It is important to recognize that any one of these early documented sites could receive controversial attention similar to that of Clarendon Street, Southampton if not identified and addressed early in the planning and development process.

Some other scenarios of site lead benefits are more benign. Take, for example, the curious case of William Winegarden, an early 19th century homesteader in Oxford County. For lack of a surveyor, Mr. Winegarden accidentally built his house on a neighbouring lot. Archaeologists, 175 years later, were diligent enough to review the Township Papers for the lot and discovered a note from Winegarden indicating what had happened. This information was further corroborated by municipal records. The Winegarden example demonstrates the potential of land records and registries to contain valuable site leads that may otherwise not get captured in other formalized documentation; in Winegarden’s case, building on the wrong lot. Provincial land surveyors’ records are another source of valuable information, particularly on the location of late-18th and early-19th century Indigenous settlements and trails.

What is currently lacking is resources to transcribe and register these critical site leads in the Ministry’s PastPort system. Until a systematic effort to do so is undertaken, commercial archaeologists should make a reasonable effort to enter site leads as they encounter them during assessments. In doing so, we can slowly build up the site lead inventory to better reflect the archaeological record of Ontario and the efforts of our predecessors, not only those who first recorded the sites but also those who created them during the course of their lives on the land.

For information on possible site leads consult:

- The Museum of Ontario Archaeology

- Huronia Museum and Huronia Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society

- Annual Archaeological Reports of Ontario (1894-95 example)

- Ontario Archaeological Society