The Loss of Material and Documentary Heritage to Fire

On September 2, 2018, a significant repository of human history was erased when Brazil’s Museu Nacional (National Museum) was destroyed by fire. What made this event particularly tragic is that the building was one of the largest museums in South America and early estimates suggest over 90% of its collections were lost. As staggering as this single loss is, history shows that this is an all too familiar event as the destruction of documentary and material heritage to fire is not uncommon.

Documentary (paper) records are particularly susceptible to fire. It should be unsurprising that large quantities of paper necessarily stored in dry environments are persistent accidental fire hazards.

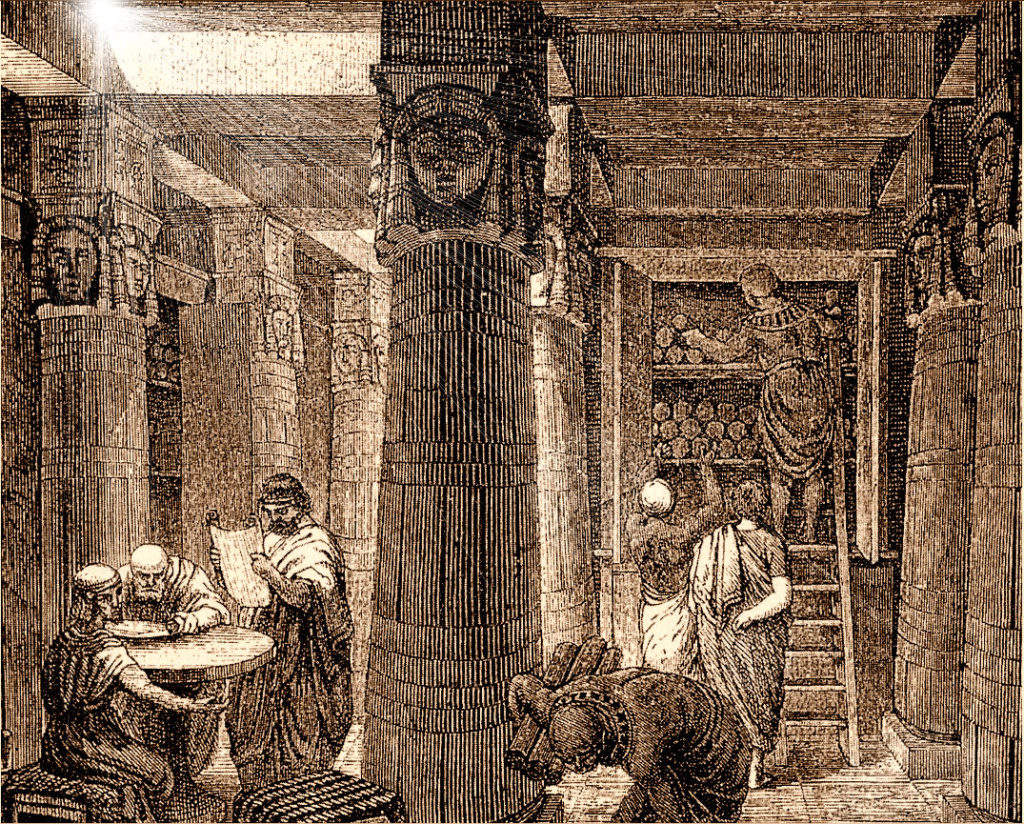

The Library of Alexandria (Source: Wikimedia Commons no alteration

Additionally and notwithstanding the inherent importance of collections themselves, the libraries, museums and religious and government institutions that house these collections are significant cultural and political symbols in their own right. This symbolism makes these collections and institutions consistent targets for vandalism, sabotage and arson, particularly during times of political conflict.

History does a good of memorializing significant losses to fire, almost in an attempt of self-preservation. The burning, by accident or design, of the Library of Alexandria in 48 BC is an early testament to the fragility of documentary records. Closer to home and the present was the loss of 24,000 books and documents when the Province of Canada’s Parliament Building in Montreal burned in 1849.

The Burning of the Parliament Building in Montreal by Joseph Légaré

Recently, archaeologists have recovered dozens of carbonized books from that fire. In 1890, the University of Toronto’s University College caught fire destroying books, documents and specimen collections. The Canadian Conservation Institute also documented four recent fire case studies in 1998.

Other significant repositories that suffered material heritage losses to fire include:

- Smithsonian Castle (1865)

- Strasbourg Municipal Library (1870)

- Irish Public Record Office (1922)

- National Personnel Records Centre, St. Louis (1973)

- Library of Jaffna, Sri Lanka (1981)

- Vijećnica, National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992)

- The Rova of Antanarivo, Madagascar (1995)

- Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2014)

- Institute of Scientific Information on Social Sciences, Russia (2015)

- University of Mosul Library (2015)

- National Museum of Natural History, Delhi (2016)

As pervasive as these losses seem to be, outside of those archivists and curators directly responsible for their preservation, the consequences of material heritage loss to fire hasn’t resonated enough to substantively address the problem. For example, prior to the loss of the Museu Nacional, Brazil also lost the Museum of Modern Art (1978) and the Instituto Butantan (2010) to fire. It is, however, tempting to suggest change might be afoot given the breadth of reflection in the present day. At the moment, Canadian news outlets are examining the state of Canadian collections such as how safe are museums in Victoria or Medicine Hat? They are also re-establishing the public merits of heritage preservation. In addition to lost cultural patrimony, it is the loss of data for future research that archaeologists and historians feel acutely.

Primary source documentation is a tremendous asset for heritage researchers. When working on historic sites, archaeologists regularly consult archives for land title, census data and other formal documentation, in addition to journals and other historical accounts. Local documentation is often stored in county museums and archives, transferred from local churches, courthouses and other institutions. Unsurprisingly, these buildings and collections also succumb to fire but don’t often receive the same scale of publicity as those examples above.

A few examples of localized heritage losses include:

- Nipigon Museum (1990) [read this!]

- Shaw Street Church BME, Toronto (1998)

- Saint-Sixte Catholic Church, Quebec (2015)

- Aberdeen (Wash) Museum of History (2018)

- Westminster Presbyterian Church, Arkansas (2018)

Nipigon Museum Fire 1990 (Image Source: Betty Brill - reproduced with permission)

The Library of Virginia catalogued known localized record losses in that state encapsulating the nature and breadth of local record destruction beyond and including fire.

"An average of 30 fires occurs in museums each year in Canada" Museum Fires and Losses - Canadian Conservation Institute (1998)

Nipigon Museum Fire 1990 (Image Source: Betty Brill - reproduced with permission)

The loss of documentation contributes to the creation of voids in our collective cultural memory. The loss of national-scale institutions such as the Museu Nacional are remarkable in that the resulting void is sudden and expansive. Fortunately, at this scale, significant efforts have been undertaken to digitize documents and collections, part of the dissemination mandates of centralized repositories.

The contemporary loss of local heritage in a church or museum fire creates similar voids, often without corresponding digitization initiatives (see here for funding of these initiatives). However, digitization is not without its own perils as evidenced by this 2018 data loss example from Memorial University; fortunately a backup of that data existed.

We have focused exclusively on fires here, but damage to heritage materials and documentation can come from a variety of sources. Flooding, earthquakes and climate change contribute to heritage degradation alongside other factors. The same sense of loss, of void creation, should also be leveled at colonialism and its impact on Indigenous heritage. The severing of oral traditions resulting from residential schools and other colonial programs in Canada should be regarded as among the most tragic, catastrophic losses of heritage documentation in North America. Just as the resilience of Indigenous cultures and communities in the face of those losses should be celebrated.

Archaeology is a unique tool for those seeking to recover from such losses. In Montreal, archaeologists are/have sifting/ed through the 169-year-old ashes of a Parliament Building, rebuilding narratives and rediscovering documents. Across Canada, Indigenous communities use archaeology to help fill some of the gaps in oral traditions caused by colonialism and gaps in written records created by colonial governments, even while archaeology, the discipline, grapples with its own colonial legacies.

Several of these reconstituted oral traditions speak to the importance of fire as a tool to shape and maintain the Indigenous landscape. Though heritage managers didn’t start these institutional fires, they are using them as a means to address inadequate and underfunded museums, archives and repositories. Time will tell if these efforts burn with enough intensity to buck the historical trends they are fighting against.