Rural Historical Farmsteads in Ontario

“Why Do I have to Dig up Grandma’s Broken Plates?!”

While there is general acceptance of the need for archaeology on Indigenous sites, archaeologists often face tough scrutiny when further work is required for the archaeological remains of rural historic farmsteads dating from the mid-19th to early-20th centuries.

To archaeologists, the value of farmstead archaeology is self-evident, but most non-archaeologists need an explanation of what valuable information grandma’s broken plates have to offer. Often clients will ask “Who cares about Grandma’s broken dishes?” Rural farmsteads differ from other sites as they: 1) are only a couple centuries old; 2) often have standing structures and available historical records; and 3) are thought to be ubiquitous.

The easy answer for most consultant archaeologists is that the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport requires it. The Standards and Guidelines for Consultant Archaeologists (2011) and the technical bulletin The Archaeology of Rural Historical Farmsteads (2014) provide direction to licensed archaeologists on these types of sites, but offer the non-archaeologist little to understand why this work is required.

Dime a dozen

Although the perception is that rural farmsteads are abundant, the reality is that they are disappearing from Ontario’s landscape. Fewer can be found as development reaches out into the townships. Some original farm homes are preserved within the fabric of urban design and formal built heritage designation, but many more are replaced by expanded urban areas. Even more disappeared decades ago as industrial farms expanded with the help of technological innovation, replacing the smaller family farm. Only a small few are documented by archaeologists, heritage consultants and landscape architects, preserving a record of their presence for future generations.

I remember when…

Quite often a local resident or the landowner can provide information about the house and property that includes a farmstead site. For example, local residents were able to provide information about the house that stood where the Sharp site was located in Ancaster and when the new house that replaced it was built. However, the archaeology revealed that the house had been preceded by an earlier homestead, one which was built in a clearing by the Indigenous peoples who had occupied the area before the settlers arrived.

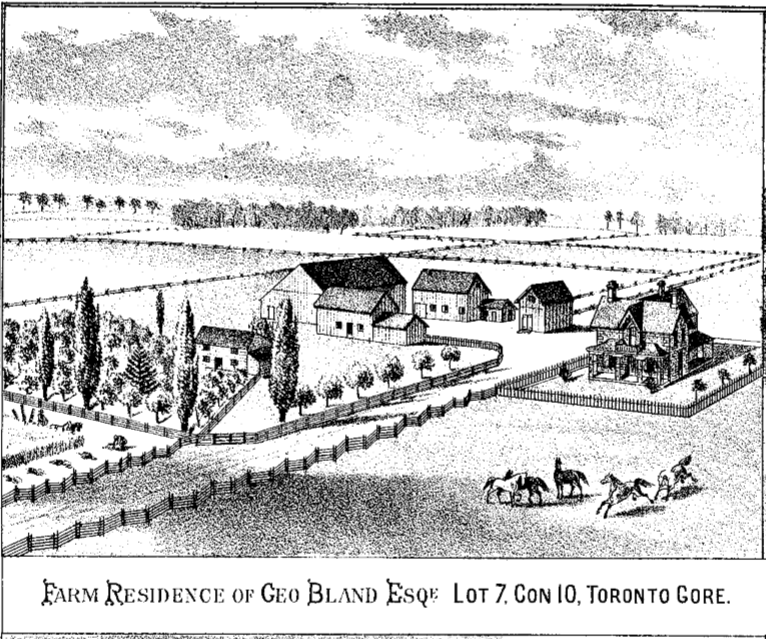

George Bland Farmstead - Historic

We know all there is to know

The value of information to be recovered from rural farmsteads is manyfold and the archaeology can provide a wealth of knowledge that cannot be found in census data, history textbooks or in the literature written during that time. Much of this period literature was written to entice new settlers to come to Upper Canada and presents an idealized vision of the past. Archaeology has the ability to provide insights into the lived daily-experiences of people in the past informing, or even contradicting, conventional stories about life in the 19th century. By studying these sites we better understand how pre- and post-confederation society in Ontario evolved from the personal and political interactions of Indigenous peoples, recent immigrants, mobile tenant farmers, and other marginalized populations (e.g., Black settlers) to today’s society.

Grandma’s broken plates can shed light on Ontario’s history specific to trade, social change, economic class, gender roles, migrations of particular groups (e.g. United Empire Loyalists and fugitive slaves) and the interactions of people of differing ethnic backgrounds. The same may be said of food remains from rural farmsteads; not only do they tell us about what was eaten, out of preference or necessity, but the study of cuts of meats can demonstrate cultural preference, identity and economic class. The artifacts from these sites can tell us how people adapted what they had in order to meet the challenges of rural life in Upper Canada. They also tell us how life differed from that of the those living in the early urban centers.

The archaeology can include colonial solutions to the challenges of pioneer life in Upper Canada. For example, a solution to address shortages in small change. The literature tells us about coins imported to address this chronic issue and these are a common artifacts on farmstead sites. But the archaeology of a site like the John Leonard (BbGd-27) site in Kingston also tells us about local solutions including hammering buttons, private issue tokens and forged tokens as currency (Ground Truth Archaeology 2011). Currency can also tell us about the connections family had with the former colonies to the south like the William Sharp site in Ancaster, Ontario (D.R. Poulton) &

George Bland Farmstead (Photo Credit: D.R. Poulton)

Associates 2007).

Grandma’s broken plates can tell us about her social and economic class in pioneer society. By understanding what the family was purchasing and where they were getting their goods, we can learn about how a family chose to spend their money. For example, the Odlum family (AkGw-389), an elite British farming family from Peel County, had the resources to purchase large and elaborate sets of matching dishes to keep up with the current popular trends, whereas the McKinney’s (AkGw-110), a middling Irish farming family, had no complete sets of dishes and the dishes they had were more economical in nature. However, the fact that the McKinney family chose to purchase more expensive bowls suggested that these had a greater significance to them than plates.

The archaeology can also help us understand the development of a farmstead like the Leflar site consisting of a log cabin at the creek’s edge of the creek in Mississauga or like the George Bland farmstead with a multi-storey brick house with a series of outbuildings surrounded by neatly ordered fields and contained in fences fronting on concession road carved through the landscape in Brampton.

At its core, Grandma’s broken plates allow archaeologists to ‘set the table’ and demonstrate how families navigated the social and economic factors of the time to create a home. They created a home where they lived and played out the daily activities of acquiring, preparing, consuming, and disposing of food and objects that had some significance to the family. These practices represent how the families understood the past, present, and future, and how the children grew up to understand their own present for the next generation.

In the end, the most telling part of the need to excavate and study 19th and 20th century sites is that they highlight how much we still don’t know about that period of time. Take AgHf-50, a site in Oxford County that dates c.1850-1864, for example. Despite collecting over 20,000 artifacts and excavating 24 cultural features, we still do not have a good understanding of this site. The documentary records suggest that it is a simple homestead; however, our findings indicate that something else was happening on this property that is not represented in available historical documents. Was this site also a store? An inn? A settlement society? Was it a work house for railway workers? At this point we don’t know. The artifacts and features can point us in some directions of further research, but without a broader synthesis and analysis of sites from similar time periods we may never figure out why this site is different than a typical 19th-century site.

Value to Present Community

The study of rural farmsteads can provide value to a community by creating a sense of belonging and place through ties to the early settlers and founding of their community; a way to tell the story of their community through the physical objects of the past. The archaeology can provide insight in to the formation of communities created by like-minded people that shared belief systems, religions and moral codes.

The artifacts recovered, when combined with census, agricultural and other data, allow archaeologists to create personal biographies; think Susanna Moodie and Roughing it in the Bush. Although not a rural farmstead, “The Ward” is just one example of how these types of studies can proliferate stories of the oft forgotten past. These stories of the lives of immigrant populations can be told and we can piece together not only their struggle to survive, but also how they retained their cultural identity in an unfamiliar landscape while at the same time adapting and prospering to a new life. In other words, the early form of Canada’s cultural mosaic – something that is still relevant today given the current political climate of immigration policy. Lost voices can once again be heard in celebration of our combined pasts by creating a sense of who we are and where we came from.

George Bland Farmstead - Well (Photo Credit: D.R. Poulton)

Recent technology and industrialization have created a disconnect whereby many people don’t know where their food comes from and they understand little about the business of farming and how our food arrives at the dinner table. Resurging in popularity today, people have become more focused on creating less of an environmental impact and the going green, buying local movements can be observed with the increase in farmer’s markets in most major cities. Organic farming is also on the increase as part of this demand. Through the archaeology of rural farmsteads, we can glean information as to how small-scale family farms worked the land in a pre-industrialized (akin to organic) way of life using small farming technology, which in turn can be used to inform organic farmers of today.

Ultimately the requirement to protect, conserve and preserve some, not all, of this type of archaeological site is about how Grandma’s broken plates can give us a picture of how people lived their daily lives through those little pieces that were left behind.

References:

ASI Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Services

2000 Stage 3 and 4 Archaeological Excavations of the Covenanter Site (AkGw-109) and the McKinney Site (AkGw-110), West Half of Lot 13, Concession 2, W.H.S., (Geographic Township of Chinguacousy) City of Brampton, Regional Municipality of Peel, Ontario. Report on File, Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.

D.R. Poulton & Associates

2004 Supplemental Report on the Stage 1-2 Archaeological Assessment of the Proposed Dolomiti Estates Subdivision, Draft Plan 21T-03010, Part Lot 7, North Half, Concession 10 Geographic Township of Toronto Gore Bram East Secondary Plan, City of Brampton, Ontario. Report on File, Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.

2007 The 2006-2007 Stage 1-3 Archaeological Assessment of the North Parcel of the Ancaster Agricultural Society Property, Part of Lots 29-30, Concession 4, City of Hamilton, Regional Municipality of Hamilton-Wentworth, Ontario. Report on File, Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.

2008 The 2007-2008 Stage 2-3 Archaeological Assessment of the Proposed Yard at Wolverton, Part of Lots 1-6, Concession 9, Blenheim Geographic Township, Blandford Blenheim Township Municipality, Oxford County, Ontario. Report on File, Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.

2011 Preliminary Excavation Report: 2009 Stage 4 Archaeological Salvage Excavations of the Odlum Site (AkGw-389), Redberry Holdings Inc. Property, City of Brampton, Ontario. Report on File, Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.

Ground Truth Archaeology

2011 Stage 3/4 Archaeological Assessment and Mitigation of the Westendorp Waste Transfer Facility: Part Lot 4, Concession IV, Western Addition, Kingston Township, Frontenac County, Municipality of Kingston. Report on File, Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.

Timmins Martelle Heritage Consultants Inc.

2015 Stage 4 Archaeological Assessment Existing Aggregate Pit Putnam Pit 8 – Blythe Dale Aggregates AgHf-50 – Location 1 Part of Lot 23, Concession 5, Geographic Township of North Oxford, Oxford County, Ontario. Report on File, Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.