There are many aspects of Indigenous community involvement in the archaeological assessment process that can be explored, but one that is a particular focus is community members involved in the archaeological fieldwork. Although not new to archaeology, the participation of Indigenous community members in Ontario archaeological fieldwork has changed rapidly since the introduction of the Standards and Guidelines for Consultant Archaeologists (2011). This change has raised several challenges.

It should be acknowledged at the outset that we comment on these challenges as non-Indigenous archaeologists who have been working closely with Indigenous communities in CRM archaeology since the inception of TMHC in 2003. Ours is an archaeological perspective, not an Indigenous one. We do not speak for any Indigenous community, nor do we assume that all Indigenous communities share the same concerns with respect to archaeology.

It is important to note that Indigenous involvement in archaeological fieldwork is often about more than the archaeology. Beyond archaeological theory and practice there are a variety of reasons for Indigenous participation in archaeology, which can include:

- Treaty and land rights including the right to manage heritage and artifacts;

- Aboriginal title;

- Information sharing and inclusion of a community perspective;

- Traditional views of artifacts and archaeological sites;

- Access to the development process and concern for the environment;

- Employment opportunities and skill development for youth in the community.

Archaeologists in Ontario are beginning to recognise these other reasons for Indigenous engagement, however, they often struggle with managing the expectations from Indigenous communities in a regulatory environment that lacks clear, explicit requirements specific to the Duty to Consult and Accommodate as it relates to cultural heritage.

Most of the attention around Indigenous community representatives in archaeological fieldwork has focused on questions related to the cost of compensation for community participation. Firmly grounded in land developer-funded budgetary constraints, these questions have tended to overshadow bigger issues related to why communities want to be involved in the archaeological fieldwork, what participation means and who has the authority to make decisions on behalf of the Indigenous community.

Published examples of Indigenous participation in archaeological fieldwork (although rare and ad hoc) can be found for some of the earliest commercial archaeology projects in Ontario (i.e. Draper site). While Indigenous involvement in archaeological fieldwork has been more common in northern Ontario, a significant shift in southwestern Ontario was marked by community members' involvement in the archaeology of Hydro One’s Niagara Reinforcement Project around 2005. While the hiring of Indigenous people directly as field crew has not been widespread and has remained fairly limited, the practice of having an Indigenous community member observe and often participate in the archaeological fieldwork has become commonplace in southern Ontario. The Standards and Guidelines for Consultant Archaeologists (2011) do not specifically require Indigenous community members to be present during the archaeological fieldwork, but this has become the most common request from communities as part of meeting the provincial requirements for engagement. The Green Energy projects from 2010 to 2013 also marked a dramatic change as numerous large scale archaeological projects across the Province provided many opportunities for Indigenous community involvement.

The Standards and Guidelines for Archaeology recently issued by the Mississaugas of the New Credit (MNCFN) demarcates the current extent of change, but also represents one of the few examples where it is clearly defined what role community members involved in the archaeological fieldwork play with respect to representing their community. It also clearly defines the processes of decision making by the MNCFN Department of Consultation and Accommodation (DOCA). Additionally, the document outlines that there are certain decisions that are for elected representatives and/or Elders within the community to make.

Experiences with community members involved in archaeological fieldwork range from full participation in the activities of archaeology to watching from a distance. Most communities however encourage their representatives to be actively involved. This is reflected in a change in terminology. The term archaeological monitor was commonplace when the Standards and Guidelines for Consultant Archaeologists (2011) were implemented by the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport in November 2010. This is characterised in the term being used exclusively in the technical bulletin Engaging Aboriginal Communities in Archaeology (2011) released by the Ministry to provide guidance related to Indigenous community engagement in the archaeological assessment process.

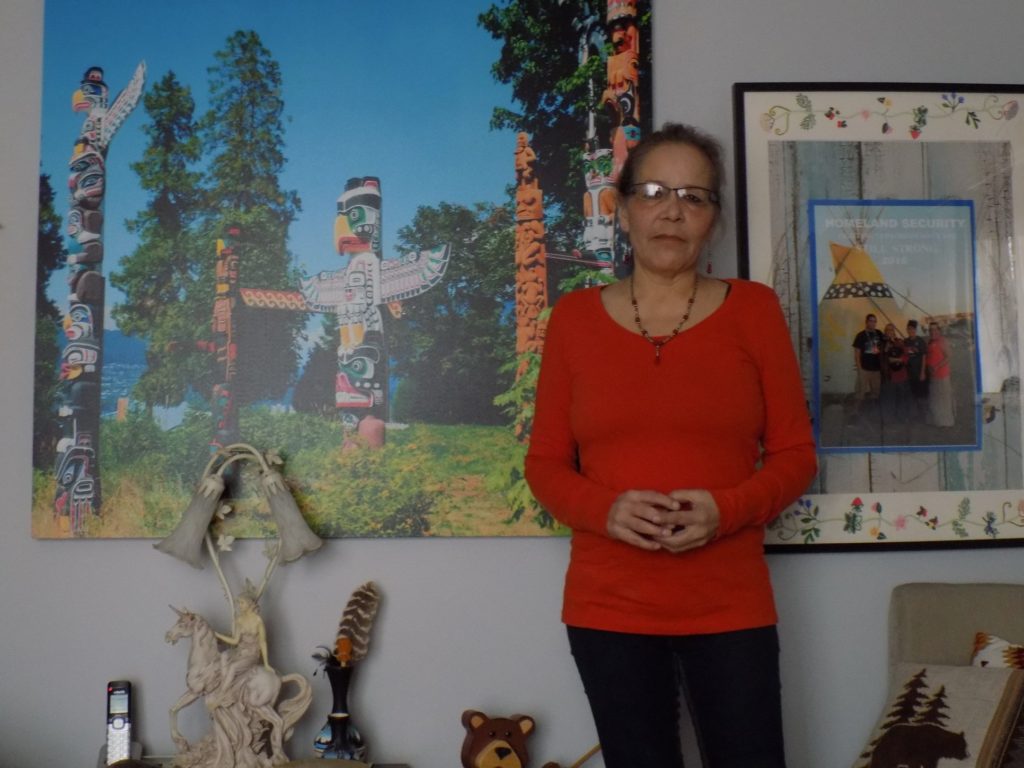

Wanda Maness, CEO Tri-Tribal Monitoring Services - Image Credit: Wanda Maness

Today, the term “monitor” is falling from common usage, replaced by such terms as liaison officer and field liaison representative to reflect the desired role of community members who not only observe the archaeological fieldwork, but also participate and report back to their communities. Whether they can speak on behalf of the community or are delegated the authority to make particular decisions is often community specific and contextual. Too often it is assumed by a consultant or client that a liaison can speak on behalf of an entire community leading to assumptions of formal approval for a particular approach, when in fact that authority rests with community consultation staff or with Chief and Council.

With the changing role for community members who are involved in archaeology also comes changes in what decisions they have the authority to speak for the community. These community members contribute not only the perspective of their community, but are increasingly knowledgeable in archaeological field methods and strategies, allowing them to provide feedback on the quality of the archaeological fieldwork being completed which, in turn, is informing Indigenous community decisions. In some instances, they have begun to regulate archaeological fieldwork by providing the on-the-ground oversight that the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport has struggled to provide.

Despite the potential challenges, there are clear benefits from having community members involved in archaeological fieldwork. Knowing who can speak for a community is critical to avoiding delays, maintaining good relationships and ensuring project success. In the absence of clearly stated roles and responsibilities from the community, archaeological consultants (and their clients) who have worked to develop long term relationships with Indigenous communities are able to identify who has the authority to speak for the community as archaeological issues arise, thus emphasizing the importance of developing relationships, creating trust and working respectfully with Indigenous communities.

Huron Wendake Museum - Image Credit: Pierre-Olivier Fortin, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

As archaeologists working in the 21st century, we feel it is important to recognize that our position as "experts" and "stewards of the past" is changing as descendant communities – not only Indigenous descendant communities – rightfully seek more input and control over the management of the archaeological record. The changing role of Indigenous community members involved in the archaeological fieldwork is a sign of this long overdue change taking place.