Lawson Site

Archaeology in the 21st Century (2012-2017) - The Story of Archaeology

From Hobbyists to Archaeologists

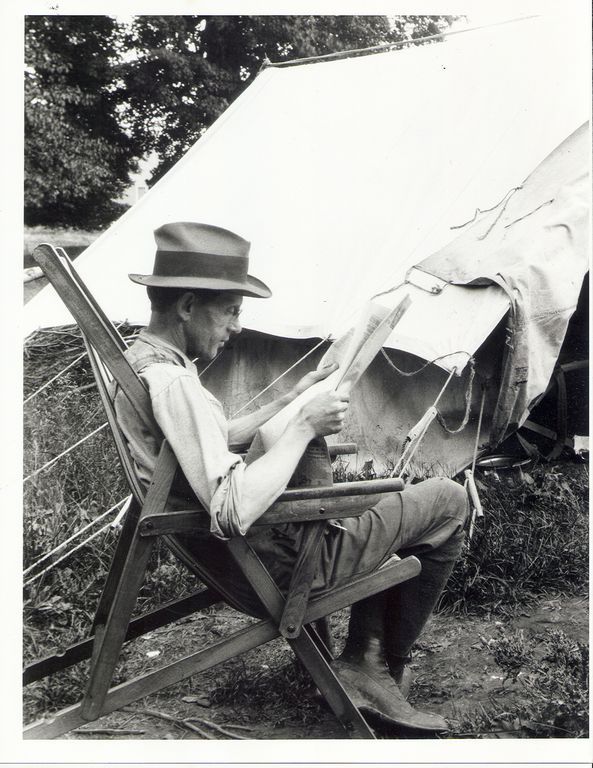

In many ways the story of Wilfrid Jury encapsulates the story of late 19th and early 20th century archaeology. The discipline began as a hobby for non-professional relic hunters such as the geologist Solon Woolverton and the farmer Amos Jury, and for Wilfrid himself when he was younger. There was very little systematic or record-worthy in the manner in which these early "archaeologists" harvested the archaeological record for their curio cabinets and exhibitions. Not until David Boyle took up his role at the Ontario Provincial Museum was it clear there was a space for a professional archaeology developed with formal methodologies and standards capable of changing through time and a motivation centered on the preserving the collective value of the past rather than enriching a personal collection.

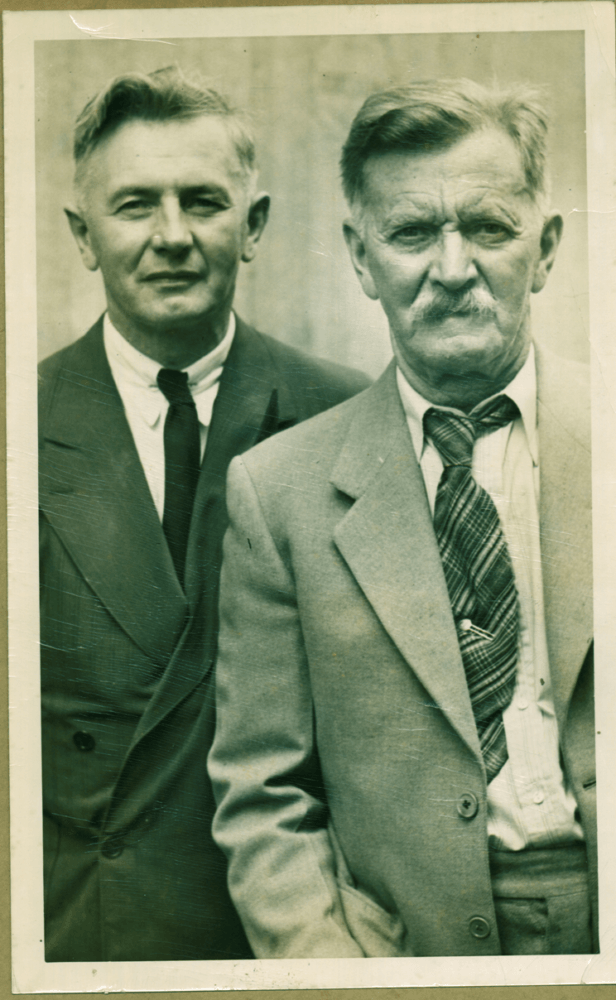

The later work of the Archaeology Division at the Geological Survey of Canada, demonstrated the early value of archaeological institutions. When Archaeology Division employee William Wintemburg began working the Lawson Site in the 1920s it represented the first time a professional and systematic methodology had been employed at the site. It is possible that the Jurys first met Wintemburg at the Lawson Site in the 1920s, though we know for sure Wilfrid started working for Wintemburg on the Southwold Site in the mid-1930s. It was there that Jury began his transition from hobbyist to archaeologist later employing systematic excavation techniques at Ste. Marie, Forget, Huronia, and elsewhere. It is not clear if Jury ever returned to excavate parts of Lawson Site after relic hunting there in the 1920s and 30s, but Jury's involvement with the fate of the site would be profound, as he played an instrumental role in convincing landowner Ray Lawson and later his son, Colonel Tom Lawson, that the Village at the confluence of Snake Creek and Medway River deserved recognition and protection.

Science by the Numbers

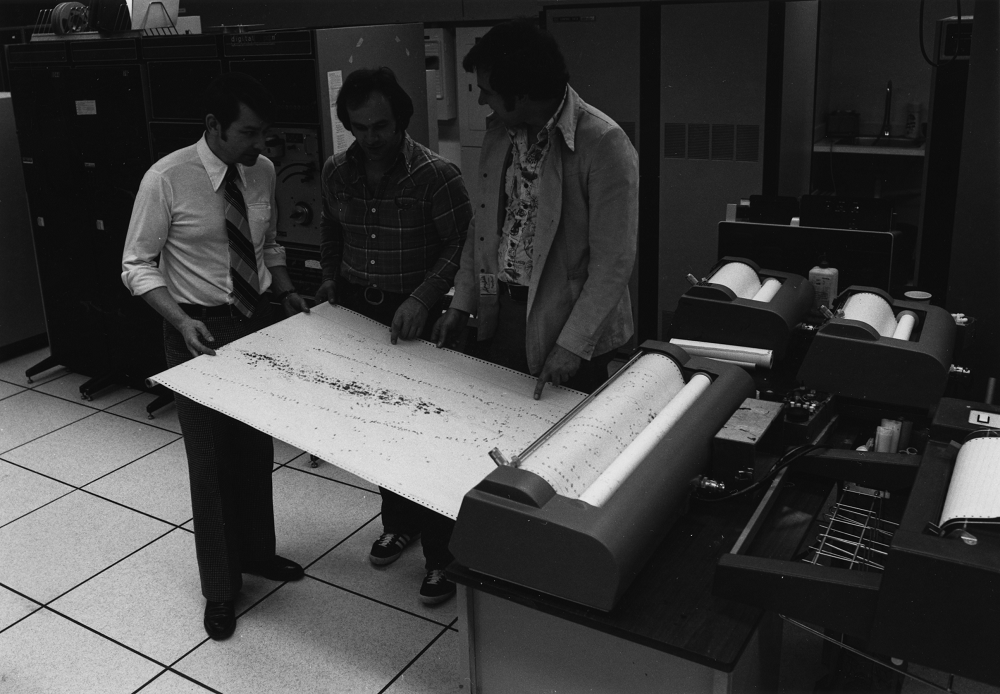

After Tom Lawson donated the Lawson Site property to Jury's early iteration of the Museum at the University of Western Ontario, the archaeological and interpretation activities at the site increased in scale and complexity. In the 1960s and 70s, the dominant paradigm, or way of thinking in archaeology, centered on archaeology as a quantitative science. Given enough data and the tools to analyze it, the thinking was, an archaeologist could begin to see patterns and make predictions about the past as expressed in the material record. This paradigm developed in concert with the implementation of computer technology in archaeology.

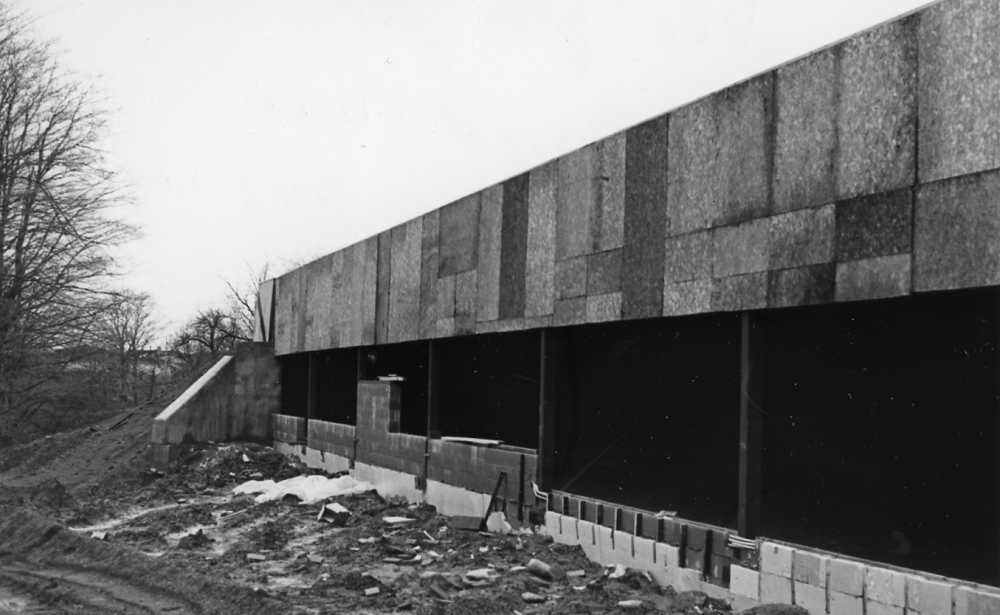

When Dr. Finlayson led efforts to build a new home for the Museum by the Lawson site, the Museum became a state of the art facility with the tools and expertise necessary to collect and analyze large quantities of data. Museum investigations at the Draper (near Pickering) and the Crawford Lake (near Milton) sites in the 1970s saw excavation and documentation on a massive scale. At the Lawson site Dr. Finlayson also applied large scale systematic excavation and mapping.

The scientific directive in archaeology towards massive data collection necessitated the documentation of as much data as possible in the process of excavation. The value of the data itself as opposed to any intrinsic heritage value in the site, influenced the development of this new form of archaeology the Museum championed: rescue or salvage archaeology which eventually became cultural resource management.

In the face of development impacts to archaeological sites, the scientific answer was to save the data, as artifact collections and as the records and forms used to document the excavation and recovery of those collections. Archaeological fieldwork, not to protect the integrity of sites but the integrity of portable data, became the justification for this new form of archaeology. At the Lawson Site, the field schools of Dr. Finlayson, Dr. Smith and Dr. Pearce taught students and the public the scientific rigors of field data collection and laboratory analysis.

In the Service of Others

Through the 1970s and into the 2000s, the Lawson Site became a touchstone for students of archaeology at Western, many of whom would go on to careers in archaeology. These students left the reconstructed palisades and shady woods of the Lawson site to make their living as professional archaeologists in a world where archaeology was much more public than it had been previously. Salvage/rescue archaeology and increasing development impacts to archaeology led to the more formalized regulation of archaeological practice, especially related to CRM archaeology. Archaeology for archaeologists now also became archaeology for government, for clients, for the public good.

Academic archaeology continued at the Lawson Site and in Ontario universities generally, even as the bulk of practice shifted to the commercial/regulatory sphere after 1980. These two spheres, academic and commercial archaeology, existing in a state of respiratory exchange where the university processed students into professionals which were inhaled by the growing commercial consultancies and governments.

Once beyond academia, many archaeologists soon realized their practice had implications beyond the priorities emphasized in their studies. Descendant communities, Indigenous groups in particular, were recognizing the space CRM created over the fate of their heritage and sometimes over development projects themselves. The archaeological drive to conserve archaeological data was interacting with the ways in which Descendant communities found meaning in their heritage.

Today, those implications of archaeology as heritage and the values of archaeology beyond archaeologists’ interests significantly shape the direction this practice follows, both as CRM and as a focus of study in universities. Material information and context remain the critical learning tools for how archaeologists come to gain insight into human pasts and make meaning from those artifacts and stains in the ground, unique to how an archaeologist can read into the past. But archaeologists also are now taught and come to know, in scholarly work and in CRM, that this is just one way of knowing the past, Moreover, caring for archaeology in Ontario and Canada today means balancing archaeological and the other values tied to this material record, and recognizing the role of Indigenous Peoples and other Descendants in deciding how to manage and care for their heritage. Once again the efforts at the Museum are helping to transform archaeology, through its changing approach to caring for and remediating the Lawson site, through its participation in and promotion of a sustainable, 21st century form of archaeological practice, and by working to ensure the Museum is as much about the contemporary people and diversity of voices who draw meaning, identity and value from the archaeological heritage, as it is about those artifacts and contexts archaeologists document to help remember the contributions of all the generations of ancestors who lived, loved and were a part of this place before us.

So, the community at the confluence of Snake Creek and Medway River – both the 500 year old village community represented by the archaeology of the Lawson Site, and the community of educators, knowledge keepers, learners and publics who gather here today – continues to shape the world around it.