We live in a pretty big country. Including land and sea territory, Canada covers 9.98 million square kilometres. That’s a vast territory consisting of thousands of ecosystems each with its own operational quirks, patterns and idiosyncrasies. These ecosystems and the landscapes that encompass them cycle on timescales that can reach far beyond a mere couple of centuries. In surveying the scale of recent Canadian land-use (residential, agricultural, forestry, mining, etc.) and the relative swiftness with which that land-use has pervaded the landscape, it can be tempting to attribute this expansion to technological advances and the “superiority” of modern land management. But this notion of “frontier”-ism, or the primacy of the recent past fails to acknowledge that this vast territory and its multitude of ecosystems were already well understood by the Indigenous Nations and Peoples of Turtle Island (what would become known as the Americas).

This comprehension, through oral tradition, included reference to cycles of environmental and ecosystem change not just on the scale of centuries but of millennia. What’s more these cycles were not just passively adapted to by Indigenous Peoples. Over hundreds and thousands of years, the ancestors of Canada’s First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples actively shaped the landscape and its ecosystems in ways contemporary society is only now just starting to appreciate.

Traditional land-use management practices (widely known as Traditional Ecological Knowledge or TEK) were refined over generations of adaptation and education, and many of these practices continue to be refined in the present day. As practicing archaeologists who have worked across Canada, the people at Timmins Martelle Heritage Consultants regularly encountered these Indigenous land management practices and technologies that shape the contemporary Canadian landscape:

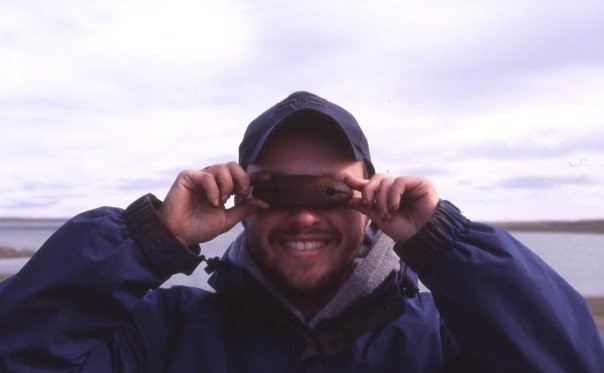

“The world’s first sunglasses, snow goggles are a type of eyewear traditionally worn by the Inuit peoples of the Arctic, to prevent snow blindness while hunting or traveling on the snow-covered tundra or spring ice. Sometimes made out of bone, ivory, or wood the small slits reduce the amount of glare and help focus the wear’s vision without having to squint. The goggles pictured are made of wood and about 1000 years old.” – Tom Porawski

Photo Credit: Max Friesen

Despite attempts to alter or end these practices through relocation, regulation and residential school interruption of inter-generational cultural transmission, many of these land management regimes persist, particularly in the North. Acknowledging these practices and seeking to understand them within the broader context of contemporary land development will serve Canada well over the next 150 years and beyond.

To learn more about Indigenous land management practices:

The New Ecology and Landscape Archaeology: Incorporating the Anthropogenic Factor in Models of Settlement Systems in the Canadian Prairie Ecozone – Gerald A. Oetelaar and D. Joy Oetelaar

People, Places and Paths: The Cypress Hills and the Niitsitapi Landscape of Southern Alberta – Gerald A. Oetelaar and D. Joy Oetelaar

Forgotten Fires: Native Americans and the Transient Wilderness – Omer C. Stewart

Bushman and Dragonfly – Gary Potts

Landscapes of Clearance – Angele Smith and Amy Gazin-Schwartz

Pioneers, Progress and the Myth of the Frontier: The Landscape of Public History in Rural British Columbia – Elizabeth Furniss

The Trail as Home: Inuit and the Their Pan-Artic Network of Routes – Claudio Aporta

Beyond the Water’s Edge: Towards a Social Archaeology of Landscape on the Northwest Coast – Jeff Oliver

The Įdaà Trail: Archaeology and the Dogrib Cultural Landscape, Northwest Territories, Canada – Thomas D. Andrews and John B. Zoe

Canadian Aboriginal Cultural Landscapes in Praxis – Thomas D. Andrews and Susan Buggey

Gwich’in Places Names, Stories, Maps – Ingrid Kritsch